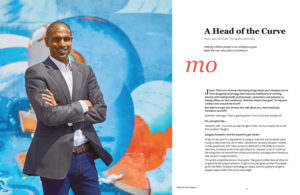

fSpace Magazine – A Head of the Curve

A Head of the Curve

Helping a billion people is an ambitious goal. Meet the man who plans to achieve it.

Words: Jason Normandale, Photography: Sabine Albers

fSpace: There are so many interesting things about your company Curve, from designing technology that improves healthcare; to working directly with leading health professionals, researchers and patients; to having offices on four continents. And then there’s that goal: “to improve a billion lives around the world”.

But before we get into all that, let’s talk about you. How would you introduce yourself?

Mo Jaimangal: That’s a good question. From a business standpoint?

No, just generally …

Hmmmm, well … I’ve never actually thought of that. You’ve stumped me on the first question! (laughs)

(laughs) Fantastic! And the questions get harder!

I’d say I’m Mo, and I’m a big believer in trying to make the world a better place, trying to help those who are in need. I started this company because I wanted to help people who don’t have access to healthcare or the ability to improve their lives, to release some of the pain they’re in. I wanted to see if I could use the things that I’ve learned from school and industry, and apply them directly to help people in tough situations.

I’m a pretty competitive person, I love sports. That goal of a billion lives will drive me to spend my life trying to achieve it. If I get to it sooner, great, but then I’ll probably go for two billion. And given technology, its impact, and how quickly it can get to people, maybe a billion isn’t such a crazy target.

You have quite the education mix with Mechanical Engineering, Computer Science and Mechatronics. Take me back to your decision to study those degrees – was it a master plan back then, an extension of childhood interests, or some kind of torture from your parents?

I’ve always been a tinkerer. I was always playing with computers, taking bikes and equipment apart and putting them back together. I was always curious how things were built.

It’s probably an immigrant family thing but my parents wanted me to be a doctor, they really pushed me to be a surgeon or a doctor in healthcare. They bought me doctor books and games, where I’d have to operate on something, so that kind of medical bend grew early. Though when I got to high school, I just thought I’d be playing basketball –

Right, in the NBA with Lebron …

(Laughs) No – the NBL. I wasn’t good enough for the NBA, but the _NBL_ … maybe. But when I started getting serious about what I was going to do in university, I put medicine down as my first choice, but secretly wanted to study engineering. And mechatronics just sounded cool.

While you were studying, you were also starting some small businesses. One in particular had strong social components such as breaking barriers, employing disadvantaged people and having a strong social reinvestment. Where did this interest come from? Why is it important to you?

I guess coming from a third world country, a pretty dangerous country –

Which country is this?

British Guiana in South America. It’s part of the Caribbean mainland south America. Lots of violence, really poor, a situation you want to escape if you can. My parents left with pretty much nothing and came to Australia when my brother and I were little boys.

There weren’t many other immigrants during the early 80’s where we lived and as a result, we experienced a lot of racism and felt alienated or substandard to everyone else. I think that feeling stuck with me for a long time, a feeling of trying to get to equality.

I have this thing about trying to make the world equitable. I think that by helping create access to things that everyone else has access to, opportunities will grow from there. That’s part of my upbringing and my experience coming here as a little boy. The experience of being different really shapes you, makes you tough. It makes you a fighter – a fighter for a cause I felt I had to overcome.

Shortly after graduating, you found yourself in Detroit as part of a leadership team for innovation and development for General Motors. Developing future technology for one of the largest automotive companies in the world sounds like a pretty sweet job with a lot of potential, but you left to start Curve. A lot of people would feel reluctant to leave the stability and security of a high profile job in an established company. What motivated you to make that decision?

Yeah, it was kind of a dream engineering job – unlimited budgets, traveling the world, cool tech, cars 10 years out. I mean you dream about that stuff as an engineering student, and I love cars so it was right up my alley.

But a problem with working on innovation in big corporations is that it’s really hard to get something that helps people or the planet into production. Those production lines are driven by business, by making as much money as you can out of each car. That’s just how most corporations are set up, to make as much money as possible for the shareholders.

It’s really disappointing when you work on stuff that would make a positive impact on the customers, like improving their driving experience or safety, but then those things don’t make it into a car. So I was never able to close the loop of building something and see it impact people. That’s why I wanted to leave and do something where I knew I’d be in control, even if it would be on a smaller scale.

You’ve told me that building companies also helped you appreciate the value of working with friends. Even now, several of your friends are directors in Curve. Talk about this value of working with friends – what is it and why is it important to you?

Friendship is bigger than running a company, and as long as you have similar goals, working style and ethics, then it’s easy. If your goals are about making money, then it’s harder. But if your goals are about improving the world, and you make money as a consequence of that, then it’s easier to work and make decisions, because everyone is passionate about making a positive change.

We just share a vision of what we’re here for. We’re not trying to dominate the world. Our vision is about those one billion lives. We can argue and have disagreements on how to get there, but as long as we keep it to a level that isn’t personal, our friendships remain intact.

We check our egos and make sure that no one is above anyone else. We’re in this together and we try to succeed as much as we can, rather than ‘I want to be bigger or better than you’. I have a lot of admiration around their morals and how they go about work.

That ego checking is backed by the team page on your website – it only shows faces and names. Why are job titles avoided in your company?

I think titles can box people in a bit and create barriers where there don’t need to be any. Particularly if you take an executive role where, if I’m CEO or CTO and you’re a developer or engineer, it automatically creates this barrier that I’m more experienced or better than you, that ‘I run the company, so don’t waste my time’.

I’ve worked in organisations like that, where people are afraid to go two levels up. For us, we want a graduate or a student to come up to us and say ‘hey, I think you guys are running your company like shit’ and I would sit down with them and say ‘tell me about that’. I want to hear what they see that we don’t. We really want to foster that openness where at anytime, anyone can call us out on anything.

That is very rare.

Yeah, it creates a shared responsibility model. Even though a handful of us run the company, as directors we want to share what we’re doing and why.

We set goals as a team – like x revenue or y profit – and we don’t hide that stuff. We want to be as open as we can. We want everyone in the company to feel comfortable sharing what they think we’re doing right or wrong.

There are a lot of products showcased on Curve’s website. One of these products is a free app, Headcheck, that helps parents and coaches identify concussion symptoms in children. There’s another that’s for health professionals to quickly and accurately diagnose behavioural conditions.

How do you decide which projects to work on? Do you strive for a balance of big long-term projects with some that are more low-hanging fruit? There must be some that are tempting because they might develop relationships or increase awareness.

Yeah, it’s a combination. There are some low-hanging apps that we get out, then there are some products we build that show what we can do, to help open doors. But because we’ve been around a while now, we’re moving into a place where we can ask questions like ‘how serious are you to getting this out to people?’ and ‘how many people will you impact?’ Our big driver is that metric, and if we’re true to that, we have to look at all our contracts through that lens.

For instance, if a project is a million dollars but it isn’t really going to get out and help anyone, whereas another project is a hundred thousand dollars but is going to impact 5,000 people, we seriously have to look at that. The million-dollar project, while it would give us great revenue, we’re probably not going to take it because it’s not going to help anyone.

When you have these large visions and goals, it’s the projects you say to no to that you prove how real you are.

Curve partners with leading hospitals in Australia and you’ve had interesting opportunities, such as observing surgery as part of your research. How did that come about and what it was like?

You can really live in a bubble where you don’t know all the things that are going on. Actually having an office inside a hospital is amazing because you’re confronted with what’s happening every day. Seeing kids who have cerebral palsy or are suffering through cancer treatment, that really motivates you to do something to help them go through their journey and have a better life.

I’ve been lucky enough to follow the head of surgery for The Royal Children’s Hospital in Melbourne into his theatre. And it wasn’t just watching the operation – it was meeting the parents and the child beforehand, talking with them and understanding what they’re going through, their emotions. I got to experience that whole journey from all points of view – the doctor, his team, the parents and the child. It really opens your eyes to the health system, where it’s great, where’s bad, where it can be improved.

It also gives you motivation from an innovative, engineering perspective: how can we take our system in Australia – one that has some of the best medical minds in the world – how can we make it better? How can we make it available to those who don’t have it?

We think about all these things, but also about really understanding the emotions people go through. When we build products, it’s not just to solve a technical problem. It’s about how do we make this person feel better about their life.

Within Fremantle, there are a lot of inspiring people helping others or promoting healthy changes. But moving the public consciousness, whether it’s for health, education or the environment is always challenging. Dealing with various levels of government as well as public entities like hospitals and universities must present some additional bureaucratic and political challenges.

Yeah, it’s hard, especially working with government or big not-for-profit organizations – they’re all very strict on how they do things. We know things can be slow and take time of slowly moving the needle and building trust. Once you’ve started to deliver and show that you’re true to your word, the doors open more easily, and people begin to trust. But that takes time and we haven’t found a way to shortcut that process.

What’s next for Curve? What are you most excited about?

We’re starting to get more visibility with government and some of our projects are getting out there and getting a lot more use. Impact is one of the key things we measure and we’re starting to see our impact numbers grow.

We’re always looking how we can accelerate the growth of our impact to people. Whether it’s through different marketing channels or continuing to focus on projects we know are going to make a bigger difference.

We’ve also started to develop our own projects, ones that don’t have a specific partner or collaborator. We’ve seen so much from the different parts of healthcare that we’ve been asking ourselves: what are we seeing that no one else is seeing? What can we look at and try to put out there? It’s exciting.

This interview is from FREMANTLE Space, a magazine that explores work, life and community in Fremantle.